Native American Pioneers in Medicine

Native American Heritage Month Roundtable

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865-1915)

As a young girl, Susan La Flesche Picotte witnessed the tragic death of a woman in her community, because a local white doctor refused to treat her. This event left a lasting impression on Susan, who went on to be the first Native American woman in the United States to receive a medical degree. She was also the first person to receive federal aid to assist her in her education. Dr. Picotte’s influence in medicine has inspired others and led to great advances for public health in Native American communities. Susan was born in 1865 on the Omaha Reservation in Northeastern Nebraska to Chief Joseph La Flesche (Iron Eyes) and his wife Mary (One Woman). Her parents invested in her education, sending her to the Elizabeth Institute for Young Ladies in New Jersey when she was 14 years old. Upon her return, she took a teaching position at the Quaker Mission School on the Omaha Reservation. During her two years teaching there, she cared for the health of an ethnologist named Alice Fletcher, who encouraged Susan to continue her education, and later helped her secure scholarships and financial aid. Susan moved back east and enrolled in the Hampton Institute, where she met resident physician Martha Waldrom, who encouraged her to apply for the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Dr. Picotte was accept and graduated a year early, at the top of her class. After a one-year internship in Philadelphia, she returned to Omaha to teach at the government boarding school, where she was responsible for the care of about 1,200 people. Dr. Picotte married in 1894 and moved to Bancroft, Nebraska, where she opened a private practice and treated both non-white and white patients. In 1913, only two years before her death, she saw her life’s dream fulfilled. She opened a hospital in the reservation town of Walthill to provide better care for those in her community.

Carlos Montezuma, MD (1866-1923)

Dr. Carlos Montezuma led a unique life from a very young age. Kidnapped from his family when he was five years old resulted in him losing his name and much of his heritage. He went on to become an accomplished physician and an advocate for the rights of Native Americans. He also reconnected with his family and heritage, advancing rights for the Yavapai people.

Born in 1866, Dr. Montezuma’s given name was Wassaja, which means signaling or beckoning. He and his family were of the Yavapai people, living near Fort McDowell in the former Arizona Territory. When Wassaja was about five years old, he was captured by raiders from another tribe and sold to a man named Carlo Gentile, who gave him the name Carlos Montezuma.

Gentile took Montezuma on his travels around the country, but later sent him to live with a man named Rev. William H. Stedman in Illinois. At 14 years old, Montezuma matriculated at the University of Illinois. He was an excellent student and graduated with a B.S. in chemistry in 1884, and then went to Chicago to earn a medical degree. It took him five years to complete medical training because he had to work in a pharmacy to support himself through school. However, in 1889, he became the second Native American to receive a medical degree in the United States.

With his medical degree, Dr. Montezuma worked for the Indian Bureau in several schools located on reservations. He was appalled at the terrible conditions and lack of medical supplies at these schools. In 1895, he moved back to Chicago and joined a private practice with a friend. It was then that he rediscovered his roots and began his career in activism for Native American rights. Remembering the terrible conditions in the schools he used to work in, he advocated for better conditions and access to healthcare. He also fought for land and water rights for the Yavapai people in Arizona and was a cofounder of the Society of American Indians. Dr. Montezuma was successful in securing reservation land for the Yavapai people in Arizona. He died in 1923 in Fort McDowell surrounded by his extended family who he reunited with after many years.

Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail (1903-1981)

Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail was among the first Apsáalooke (Crow) people to pursue higher education. She was educated in mission boarding schools, where she was expected to give up her native language and culture. Instead of conforming, she maintained her Apsáalooke heritage and went on to pursue a career in nursing to improve the lives and health of many Native American people.

Born in 1903, she was orphaned from a young age, and attended a boarding school on the Crow reservation. As the only child who spoke English, she often served as a translator at the school. After leaving the reservation school for Oklahoma with her missionary foster parents, Susie Walking Bear briefly attend a Baptist school until her guardian Mrs. C.A. Field sent her to Northfield Seminary in Massachusetts.

She continued her education at Boston City Hospital’s School of Nursing and graduated with honors in 1923. After finishing her training at Franklin County Public Hospital in Greenfield, Massachusetts, she became the first person of Crow descent to become a registered nurse.

After working with other tribes, Susie Walking Bear returned to the Crow Reservation and married Thomas Yellowtail. She first worked at the government-run hospital at Crow Agency and then travelled as a consultant for the Public Health service and was shocked by the poor conditions she saw in several different facilities. She noted there were many unmet health needs, barriers in language between tribal elders and doctors, and a need for cultural competency in treatment. Seeing the immediate need for reforms in the Indian Health Service, she documented what she saw, and created the Community Health Representatives Outreach Program.

Throughout her career, Yellowtail served on Indian health and education councils at the tribal, state, and federal levels. She was also an appointee to the President’s Council on Indian Education and Nutrition and the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s Council on Indian Health. She was passionate about the importance of education in healthcare. She was also dedicated to preserving Crow culture and participated in many cultural events. Because of her great work and the improvements she made in healthcare, Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail received the President’s Award for Outstanding Nursing Health Care. Among the Crow people, she is known as “our bright morning star.”

Dr. Annie Dodge Waukena (1910-1997)

Annie Dodge was born into the Tse níjikíní (Cliff Dwelling People) Clan of the Diné (Navajo) Tribe. She went on to study public health and became an activist for health and welfare in the Navajo Nation. Because of her efforts, many people received better care.

The Spanish Flu was one of the worst epidemics in history, claiming the lives of millions around the world. When the Spanish flu swept through her community, Annie Dodge Wauneka was only eight years old. After surviving the flu herself, she immediately began helping others in her community, and discovered a passion for healthcare.

In 1951, Annie Dodge Wauneka was one of the first women elected to the Tribal Council, where she made many efforts for health and welfare in the community. One effort was creating an English-Navajo medical dictionary to improve communication between patients and providers. She dedicated herself to providing information about tuberculosis and influenzas, improved sanitation and living conditions on the Navajo Reservation, and served on advisory boards to the US Surgeon General and the US Public Health Service. In 1963, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her service to her community.

Annie Dodge Wauneka’s works have made lasting improvements in public health. Her efforts and dedication to her community made her an inspiration to others. She is referred to as “our legendary mother” by Albert A. Hale, the president of the Navajo Nation.

Anne Lanier, MD (1940 – Current)

Dr. Anne Lanier is a champion for public health in the state of Alaska, and was recently inducted into the Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame. She started her career in 1967 at the Alaska Native Medical Center. Through her work as a family practice physician, medical epidemiologist, researcher and administrator, Dr. Lanier dedicated her life’s work to improving the health of Alaska Native people.

Dr. Lanier witnessed many lives lost to cancer in her community and started research to address the problem. By 1974, she created the Alaska Native Tumor Registry, which collects information about Alaska Native people diagnosed with cancer. Her registry is now one of 18 registries used by the National Cancer Institute to determine cancer rates and patterns across the US. Dr. Lanier’s data and research has resulted in significant declines in incidence and mortality rates in colorectal, pediatric liver, and cervical cancer among Alaska Native people.

Dr. Lanier also founded the Alaska Native Epidemiology Center and the Alaska Native Health Consortium’s Office of Alaska Native Health Research. She conducted medical research for the State of Alaska, Alaska Native Medical Center, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the University of Alaska Anchorage. Her efforts inspired many other researchers and led to many more people pursuing careers in medical research. She also personally funds a scholarship program for students looking to earn degrees in public health.

Journalist Lael Morgan met Dr. Lanier in the 1960s, saying of her, “She was way ahead of her time doing what she did for Alaska Native children. Dr. Lanier has never stopped asking ‘why’ and has not stopped being an advocate for improved health for Alaska Native people.”

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord (1958-Current)

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord combines traditional Navajo medicine practices with western medical science to provide holistic and culturally competent healing to patients. Dr. Arviso Alvord was the first Navajo woman to become a board-certified surgeon. After graduating from Stanford School of Medicine, she returned to New Mexico to work with Navajo patients. While there she discovered that she needed further knowledge of traditional medicine to help her patients heal completely. As she said, “Although I was a good surgeon, I was not always a good healer. I went back to the healers of my tribe to learn what a surgical residency could not teach me. From them I have heard a resounding message: Everything in life is connected. Learn to understand the bonds between humans, spirit, and nature. Realize that our illness and our healing alike come from maintaining strong and healthy relationships in every aspect of our lives.” Dr. Arviso Alvord is still a surgeon working in New Mexico trying to create a harmony between western and Navajo medicine. She works with patients and their families and takes a holistic approach in order to heal, rather than ‘fix’ her patients. She believes hospitals can make small changes to improve outcomes for patients, such as providing access to nature or removing things that cause stress.

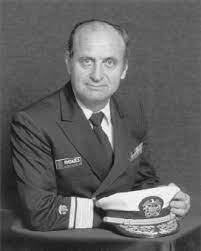

Everett R. Rhoades, MD

Dr. Everett R. Rhoades is a member of the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma and became the first Native American person to be the director of the Indian Health Service (IHS). During his 11-year term, the IHS saw many new projects completed and funding added. Six new hospitals were built in addition to several ambulatory care centers.

Under Dr. Rhoades’ leadership, the Congressional budget for IHS tripled. This allowed for significant improvements in public health for Native Americans, including the increase of ambulatory care and the expansion of dental care.

Dr. Rhoades also founded the Association of American Indian Physicians, an organization that is still working to improve public health. He also served as director of the Native American Prevention Research Center and continues to serve on the Board of the Oklahoma City Indian Clinic and IHB. Dr. Rhoades is also an accomplished author of more than 100 scientific papers.

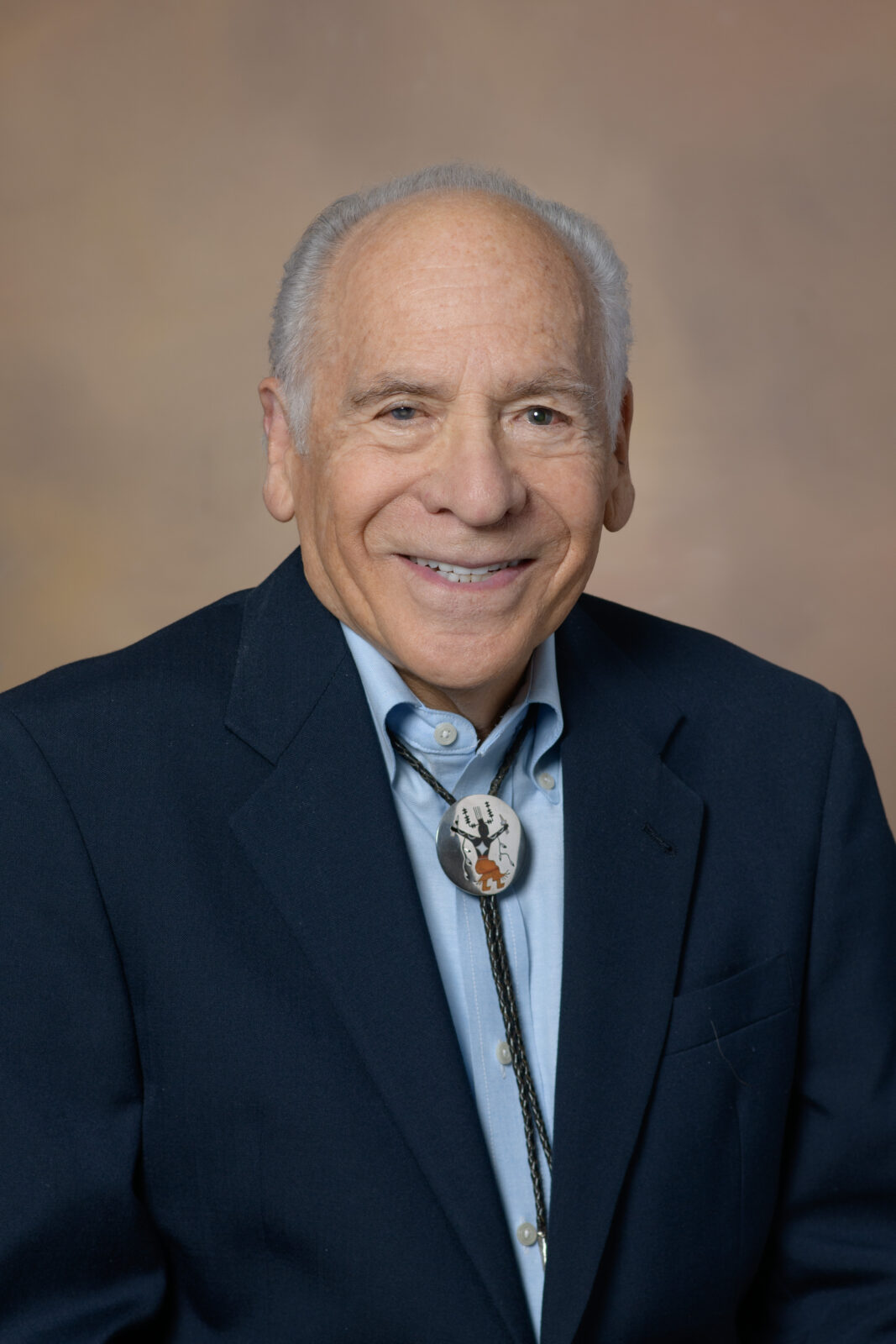

Lawrence Z. Stern, MD

Lawrence Z. Stern, MD, a Senior Fellow of the ANA, is an emeritus professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and founding Director of the Mucio F. Delgado Clinic for Neuromuscular Disorders. He received his medical degree from Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons and did his residency training in neurology at the University of California in San Francisco. He has authored and co-authored many scientific publications and served as Director of Research for the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Dr. Stern served in the USPHS Indian Health Service in Mescalero, New Mexico and Fort Defiance, Arizona, as well as on the President’s Advisory Committee on Indian Affairs at the University of Arizona.

Jeff Henderson, MD, MPH

Dr. Jeffrey Henderson is Lakota and a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. After completing his Master of Public Health at the University of Washington in 1999, he moved back to western South Dakota to work on addressing underlying determinants of health in Native American communities there.

It was then that he founded and now directs the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health. Through his organization, Dr. Henderson has championed scientific research and provided mentorship for American Indian and Alaska Native investigators. The center has led community efforts that have successfully reduced smoking, better identified cancer risks, addressed environmental disparities, and promoted traditional Lakota healing.

Dr. Henderson also led a clinical trial to test strategies for preventing cardiovascular disease among high-risk people in Native American communities; the research ultimately led to a revision in guidelines for type 2 diabetes management. Dr. Henderson continued to serve as a mentor for more than 50 trainees in the Native Investigator Development Program, allowing future physicians of Native American and Alaskan Native descent to begin careers in public health.

Nicole Stern, MD, MPH, FACP

Dr. Nicole Stern is a member of the Mescalero Apache Tribe of New Mexico. She is the first member of her tribe to become a physician. She earned her medical degree and completed a residency in Internal Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. She was a fellow in Primary Care Sports Medicine at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City, and has a master’s in public health degree in health management from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She was a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard Medical School and her practicum project focused on American Indian physician workforce development.

Currently, Dr. Stern is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medical Education at the California University of Science and Medicine (CUSM) while working as an urgent care physician. She is a fellow of the American College of Physicians and has extensive experience with the Association of American Indian Physicians (AAIP), having served as President-Elect, President, Immediate Past President, and a two-time At-Large-Director of the Board of Directors. As a recent liaison from AAIP to the Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) Committee on Student Diversity Affairs, Dr. Stern continues to serve on national committees with the AAMC to collaborate on strategic plans and initiatives that emphasize the importance of including American Indians and Alaska Natives within the national conversation around workforce development and medical school diversity.

Yvette Brown-Shirley, MD

Dr. Brown-Shirley is originally from northern Arizona and completed her undergraduate education at Arizona State University. She then went on to receive her medical degree from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and returned to Arizona complete her child neurology residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and neurology fellowship at Barrow Neurological Institute. Most recently, Dr. Brown-Shirley was a Clinical Assistant Professor of Neurology at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health before returning to her home state to join the Barrow Neurological Institute’s Brain Injury and Sports Neurology Center. She is board certified in Neurology–Child Neurology and Brain Injury Medicine by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. As an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and a first-generation physician, Dr. Brown-Shirley is proud of her heritage and passionate about improving culturally sensitive care and access to neurological services for Indigenous communities.