Hispanic Pioneers in Medicine & Science

Carlos Juan Finlay, MD (1833-1915)

Solving the yellow fever mystery

Yellow fever is a horrible disease, causing such terrifying symptoms as bleeding from the mouth, vomiting, and organ failure. By the late 1800s, intermittent outbreaks had taken some 150,000 lives in the United States, and in Cuba, where Dr. Carlos Finlay was born, it was a near-constant terror. After graduating from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1855, Dr. Finlay was drawn to numerous topics, but he found none so compelling as exploring the cause of yellow fever. At the time, experts thought they knew the culprit: filth in the air or on clothing. Dr. Finlay, on the other hand, noticed intriguing correlations between yellow fever epidemics and increases in the mosquito population. In 1881, he presented his mosquitos-as-vectors theory to scientific conferences in Havana and Washington, D.C. — and was met with ridicule. In 1898, the United States wrested Cuba from Spain in the Spanish-American War, but its troops suffered more deaths from infectious diseases than from combat. Desperate, the U.S. Army turned to Finlay for help and was able to greatly reduce outbreaks by applying some of his ideas about mosquito control, such as destroying larvae in stagnant water. Dr. Finlay’s insights enabled the completion of the Panama Canal, which had been disrupted repeatedly by outbreaks. William Gorgas, MD, who headed public health efforts there and would later serve as U.S. surgeon general, expressed great admiration for Dr. Finlay’s thinking. In fact, he called it “the best piece of logical reasoning that can be found in medicine anywhere.

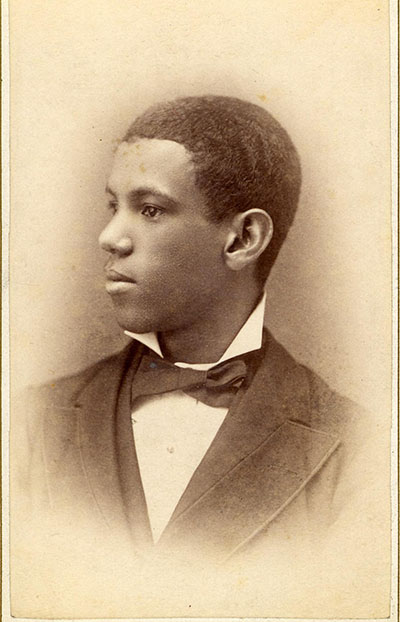

José Celso Barbosa, MD (1857-1921)

An independent Puerto Rican

Dr. José Celso Barbosa faced discrimination more than once in his lifetime. But the same determination that propelled him past those obstacles allowed him to help countless others. In 1875, encouraged by his aunt, “Mama Lucia,” Barbosa left Puerto Rico for New York City to further his education. A brush with pneumonia there spurred his interest in medicine, but admissions officials at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons rejected his application.

The letter refusing him read, “At a faculty meeting held last night it was decided not to receive students of color.”Dr. Barbosa was undeterred. In 1880, he graduated with honors from the University of Michigan as the first Puerto Rican to receive a medical degree in the United States.Dr. Barbosa went on to care for soldiers during the Spanish-American War through the Red Cross and to treat many poor patients across Puerto Rico. Dr. Barbosa even articulated a need for employer-based health care insurance, which was a radical idea at the time.

Later in his career, Dr. Barbosa founded a party that urged U.S. statehood for the island. For that leadership, Dr. Barbosa has been dubbed the “father of the Puerto Rican statehood movement.”

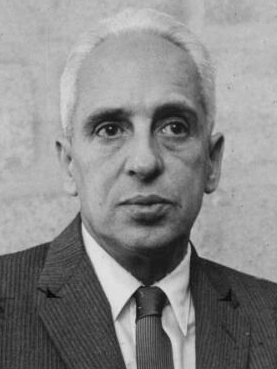

Severo Ochoa, MD (1905-1993)

Unraveling RNA

Dr. Severo Ochoa’s interest in biology was sparked by his idol, Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist and fellow Spaniard Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Decades later, Dr. Ochoa would himself enter the halls of Nobel fame. Dr. Ochoa graduated from the University of Madrid’s medical school in 1929 and then pursued cutting-edge research in several different countries. In 1942, he took a position at the New York University (NYU) College of Medicine, where he remained for more than 30 years.

Dr. Ochoa’s resume spans several domains of biochemistry and molecular biology, from photosynthesis to vitamin B’s function in the body. It has been said that in 1931, Dr. Ochoa fell in love twice: with his future wife and with the study of enzymes. Dr. Ochoa’s discovery of an enzyme that can synthesize ribonucleic acid was a vital advance in the breaking of the human genetic code. In recognition of his work, in 1959 he became the first Hispanic American to win the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

In accepting the prize, Dr.Ochoa expressed gratitude for his mentors, students, and adopted country. But mostly he lauded science’s place in elucidating fundamental questions. Though “we may never find the clue to the nature or the meaning of life,” he said, “we may look forward with confidence and anticipation to a much better comprehension of many of its riddles.”

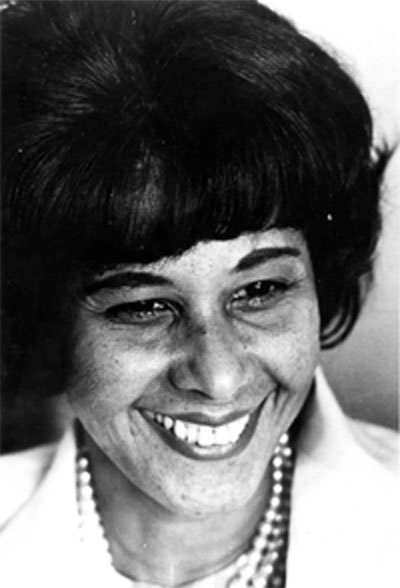

Ildaura Murillo-Rohde, PhD, RN (1920-2010)

Changing the face of nursing

“The Hispanic whirlwind” — that’s what Dr. Ildaura Murillo-Rohde was dubbed for her work as a powerhouse advocate, nurse, therapist, and educator. Born to a family of health professionals in Panama, Dr. Murillo-Rohde studied nursing at the Medical and Surgical Hospital School of Nursing in San Antonio, Texas, where she was dismayed by how few Hispanic nurses were available to serve a large Hispanic population. After graduating in 1948, she went on to pursue several other degrees in education and psychiatric nursing, including a PhD from NYU in 1971.

Over her career, Dr. Murillo-Rohde wrote about a broad range of issues from single parenthood to same-sex couples. She also reached several professional heights, including becoming the first Hispanic dean of nursing at NYU. But one of her greatest achievements was creating the National Association of Hispanic Nurses (NAHN) in 1975. She felt strongly that the country needed an organization to attract Hispanic people to nursing as well as to support their unique concerns and those of the communities they served.

“I saw that I was the only Hispanic nurse who was going to Washington to work with the federal government, review research and education grants, etc.,” Dr. Murillo-Rohde later noted. “I looked behind me and thought: ‘Where are my people?’”

For her creation of NAHN and numerous other leadership roles, the American Academy of Nursing named Murillo-Rohde one of their living legends in 1994.

Helen Rodríguez-Trías, MD (1929-2001)

Fighting sterilization abuse

From caring for low-income children in the South Bronx in New York City to establishing appropriate treatment for HIV and/or AIDS patients in New York state and promoting women’s health around the world, Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías was an outspoken activist and pioneering public health leader.

In 1970, a decade after graduating from the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías began championing quality care and cultural awareness for minority populations at the Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx, where she became head of pediatrics. One issue of great concern to her throughout the 1970s was government-led programs that coerced women, including minority women and those with physical disabilities, to undergo sterilization. Dr. Rodríguez-Trías went on to co-found the Campaign to End Sterilization Abuse, which led to strict federal guidelines for consent in 1979.

In the 1980s, she focused on helping mothers and children suffering from HIV and/or AIDS, heading the New York State Department of Health’s AIDS Institute. There, she helped establish standards of care that became a model for the whole country. In 1993, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías became the first Latina to preside over the American Public Health Association, where she used her position to promote health equity and women’s rights.

Toward the end of her career, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías co-directed the Pacific Institute for Women’s Health, where she bolstered women’s health in Latin America, Africa, and elsewhere. Before her death, she articulated an intense wish: the global recognition “that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life.”

Alberto Portera-Sánchez (1928-2019)

Pioneer of Modern Spanish Neurology

Early in the 20th century, Spanish neuroscience had a high international profile, personified by Dr. Santiago Ramon y Cajal. He was a winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine and last year his publications were cited 1,559 times, 85 years after his death. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) proved disastrous for neuroscience because of the exile of some of the most eminent and many promising scientists. Dr. Pio Rio Hortega, discoverer of microglia, ended up in Argentina, and the physiologist Dr. August Pi Suñer in Venezuela and then Mexico. They are but two of the many exiles. Neuroscience and neurology entered a long penumbra under the Francisco Franco regime.

Dr. Portera-Sanchez did part of his training in the United States and gained a faculty position. However, he returned to Spain to become the founder of modern Spanish neurology. He linked it internationally as demonstrated by his role in the World Federation of Neurology and the symposia that he organized, including a pioneering and memorable one on neuroplasticity. He was also leader in trying to link the brain with the arts and humanities. He organized a series of colloquia on “El cerebero en si mismo” (roughly translated “The brain in itself”) that featured a neuroscientist and an eminent artist or humanist. One example was a neuroscientist specializing in vision and a leading Spanish artist. I was paired with Cristobal Halffter, a Spanish leading composer on the topic “Music and the brain.” The presentations and commentaries were published as booklets.

He was a respected art collector and critic. He recognized talented young artists early in their careers and bought their paintings when they were affordable. He often wrote and commented on art, including publishing a book on the subject.He had many pupils, admirers, and friends. He hosted innumerable international guests at his country home with his gracious wife Catherine.

Antonia Novello, MD (1944-Current)

Fighting for the vulnerable

When Dr. Antonia Novello became U.S. surgeon general in 1990, her name was etched in two history books: one for Hispanic people and one for women. As a child in Puerto Rico, Dr. Novello suffered from a congenital digestive condition that her family could barely afford to treat. That experience motivated her to study medicine and ensure that care was available to all.

After earning her medical degree from the University of Puerto Rico, Dr. Novello pursued pediatrics for a while but found the field too heart-wrenching. “When the pediatrician cries as much as the parents do, then you know it’s time to get out,” she said. Instead, she pursued a career in public health, working her way up at the National Institutes of Health for decades and eventually catching the attention of the White House. As surgeon general, Dr. Novello focused on protecting the young and the vulnerable, addressing such issues as underage drinking and cigarette ads that targeted children.

Although Dr. Novello experienced a dark moment in 2009 when she faced claims of mishandling funds, she has been widely lauded for her work battling health inequities among the poor and minority groups. Dr. Novello noted the powerful call she felt to help others. “Service is the rent that you pay for living,” she said at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in 2016.

Jane Delgado, PhD (1953-Current)

Empowering millions

Jane Delgado’s knack for listening to and helping others was already clear in the fifth grade. That’s when a teacher recommended that she pursue a career in psychology. Delgado did go on to become a psychologist — but she also battled racial and ethnic inequities, taught countless people how to care for their health, and led the National Alliance for Hispanic Health (NAHH) as its first woman president. Early in her career, Delgado worked at promoting minority health at the Department of Health and Human Services. There, she made key contributions to the first U.S. effort to plumb health disparities, the landmark 1985 Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health.

That same year, Delgado took the helm of the organization that would become the NAHH, where she still serves decades later. Today, the association’s members provide services to some 100 million people annually, with projects ranging from smoking cessation programs to outreach promoting Hispanic participation in clinical trials and a recent bilingual campaign on COVID-19 precautions.

Delgado has also produced more than a dozen health-related books. Among them is the groundbreaking Salud: The Latina Guide to Total Health, first published in 1997, which encouraged women to focus on self-care. Years after she headed off to college on her own — her Cuban-born mother worked in a factory and couldn’t afford time off — Delgado gave the commencement speech at her alma mater, the State University of New York at New Paltz. In her speech there, she said, “For me, living a good life is about one thing, making a positive difference in the lives of others.”

Julio Frenk, MD (1953-Current)

Toward worldwide well-being

When his grandparents fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Mexico offered a safe haven. “The generosity and kindness of strangers in a foreign country made my life, and my family’s life, possible,” he said. “Studying medicine, public health, and education has given me the opportunity to try and leave this world better than I found it.” Frenk now presides over the University of Miami — the first Hispanic person to do so — and is recognized as an eminent authority on global health.Among his public service roles was serving as Mexico’s Minister of Health in the early 2000s. In that position, he expanded health care to more than 55 million previously uninsured people.

Frenk also served as dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health from 2009 to 2015. There, he encouraged faculty and students to address what he identified as the world’s greatest health threats: poverty and humanitarian crises, failing health systems, social and environmental dangers — and pandemics. In all his work, Frenk has been guided by the belief that evidence should underpin policy.

In receiving the Frank A. Calderone Prize, public health’s most prestigious honor, he said: “We become exemplary as we uphold the value of basing decisions on rigorous evidence, rather than ideological prejudice, and as we reaffirm our commitment to the pursuit of truth, no matter how complex and contradictory it may be.”

Nora Volkow, MD (1956-Current)

Insights into addiction

For decades, drug abuse was typically seen as a sign of personal weakness. But addiction is now understood as a brain disease, thanks largely to Dr. Nora Volkow’s creativity inside the laboratory and her powerful messaging outside of it. A prolific researcher — she has published more than 780 peer-reviewed papers — Dr. Volkow has led the National Institute on Drug Abuse since 2003.

Dr. Volkow’s journey into addiction science began as a medical student in Mexico, where she first saw patients harmed by alcohol and drug use, from cirrhosis patients to drunk-driving victims. It bothered her deeply that “we would treat them, but we never addressed the cause that brought them there,” she said. In 1981, Dr. Volkow went to New York University for her residency in psychiatry, lured by access to a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner. As someone who thought endlessly about thinking, she says, she “went wild” over the possibility of glimpsing the brain’s hidden processes.

Over the decades, in addition to her addiction work, Dr. Volkow would go on to make contributions to the science of imaging as well as to such diverse topics as the neurobiology of obesity and the effects of cell phones on brain metabolism. Dr. Volkow’s work on addiction is also personal. A beloved uncle was ostracized because of his alcoholism, and her grandfather had been an alcoholic and had died by suicide. “Drug addiction is a disease,” she says.

Serena Auñón-Chancellor, MD (1976-Current)

From space to COVID-19 wards

As a NASA astronaut, Dr. Serena Auñón-Chancellor had the opportunity to spend days on the bottom of the ocean and hurtle through space high above the Earth. But treating patients during the COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on her as well.

Dr. Auñón-Chancellor, the first Hispanic physician to travel to space, spent six months in 2018 conducting research aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Her work there included conducting experiments related to Parkinson’s disease and cancer. “What people don’t realize is that … 70% of that [research] is to specifically benefit health down here,” she said. Dr. Auñón-Chancellor fulfilled her childhood dream of becoming an astronaut in 2011. Before that, she completed medical school at the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston in 2001 and a master’s degree in public health at the university’s Medical Branch at Galveston in 2007.

Since completing her flight mission, Dr. Auñón-Chancellor has been treating patients and training internal medicine residents at LSU Health Sciences Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Dr. Auñón-Chancellor says her time aboard the ISS taught her many invaluable lessons, including two that have been essential during the COVID-19 pandemic: self-care and teamwork. Caring for coronavirus patients and traveling to space were extreme challenges, but in both, she felt strongly that she was “performing a tremendous service and fulfilling a sense of purpose.”