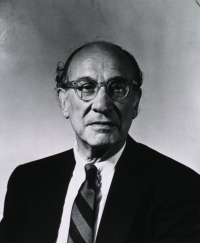

Louis Sokoloff, MD

Member Since 1966

Date of Death: July 30, 2015

Louis Sokoloff, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health who made major contributions to the technique of positron emission tomography, which makes the activity of the living brain visible, died July 30 at a hospital in Washington. He was 93. His daughter, Ann Sokoloff, confirmed the death but did not disclose a cause. Positron emission tomography, commonly known by the acronym PET, became a practical tool for tracing brain activity by the late 1970s and was hailed as a revolutionary method for detecting, managing and treating major disorders of the human brain. Over a long career in science and medicine, Dr. Sokoloff embodied the two major forms of treating mental disorders; he had provided the “talking cure” of psychotherapy, and he became a leader in studying the workings of the brain through chemistry and physics. After his early involvement in face-to-face psychotherapy of the sort that Sigmund Freud might have recognized, Dr. Sokoloff later worked to apply the techniques of the hard sciences to the mechanisms of thought and feeling.

PET, which he helped develop, involves the application of ideas from nuclear physics to the biology and physiology of the brain. Blood flow in the living brain is traced by detecting the signals from radioactive molecules introduced into the bloodstream. Mapping such phenomena as blood flow and metabolic activity, and associating them with the working of the brain, sheds new light on the old question of philosophy and psychology: What is the relationship between mind and body, between thought and chemistry, between feelings and physics? Dr. Sokoloff’s work brought him widespread recognition and honors that might have seemed beyond the imaginings of the South Philadelphia neighborhood where he was born to Eastern European Jewish immigrant parents on Oct. 14, 1921.

In recollections of the “tough neighborhood” of his boyhood, he told of belonging to the “Third Street Gang,” which had “prearranged rumbles” with the gang from the next street, firing parts of paper clips at each other, with rubber bands. Such conflict continued, he said, until the misfortune of which children are constantly warned came to pass. One of the combatants lost an eye. Finishing first in his public high school class brought him a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania, from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1943. During World War II, he was further schooled as a physician on an accelerated three-year program because of the needs of the Army, in which he was enlisted as a private. Along with fellow medical students, he was trained to salute and march, and he was instructed in such matters as map reading, he said, and “how to stop tanks.” His Army pay enabled him to meet his tuition bills, and he received a medical degree in 1946 from Penn. He was an intern the next year at a Philadelphia hospital. During the internship, he married Betty Kaiser, a Navy nurse. After his intern year, in which he did work in neuropsychiatry, he went on active Army duty, soon being installed as head of neuropsychiatry at an Army hospital at Fort Lee in Virginia. There, he said, he read all the material available, studied Freud, and with the meager training he had had, tried to do his best for his patients. Success stories that he recalled decades later included the soldier who recovered the use of a paralyzed arm, the amnesiac whose memory was restored and the nymphomaniac who gave up sex for Lent. Such obvious associations between talking and biology in those and other cases aroused in him, he recalled, a curiosity about the connection between mind and body, and between a physician’s words and the physiological and biochemical mechanisms of brain disease.

It was research into those areas that he pursued during his years at NIH, where in 1953 he became a member of the cerebral metabolism section in the neurochemistry laboratory at the National Institute of Mental Health. It was there that he began delving into biochemistry, which he said “seduced me” away from physiology and further whetted his interest in the relationship between brain chemistry and function. For the advancement of such study, he said, he needed a way to make quantitative measurements of the metabolism of the thinking part of the living brain. The idea on which he settled in time was to scrutinize the brain’s use of glucose, which was seen as the key to assessing the brain’s energy metabolism. To measure the flow, consumption and use of glucose, the aid of radioactive molecules was enlisted. By precise monitoring of molecular radiation levels, data could be obtained about the energy intake and consumption of the brain. One of the principal contributions made by Dr. Sokoloff involved his creation of a safe and effective radioactive “tracer molecule,” 2-deoxyglucose. One of the first of its kind, it satisfied the requirements of both the functioning brain and measuring equipment used by scientists.

Through Dr. Sokoloff’s work, metabolic maps were produced of the nervous system in its various states of activity. Based on his findings, it was possible without opening the skull to create images of the brain at work. Positrons are one of the keys to the technique. Positrons give their name to the method of positron emission tomography. Positrons are positively charged electrons, but they are not the particles detected by PET equipment. Instead, positrons induce the radioactive tracer molecules to emit gamma rays, and it is those that are detected and used to chart brain function. The approach was hailed by scientists as a means of showing the differences in chemistry and physiology between the normal brain and the brain that has slipped into disorder. Dr. Sokoloff, who lived in Silver Spring, Md., was a past president of the American Society for Neurochemistry and the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. He was a 1981 recipient of the prestigious Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. His wife died in 2003. Their son, Kenneth Sokoloff, a noted economic historian, died in 2007. Besides their daughter, of Kensington, Md., survivors include two grandchildren.

Published in the The Washington Post in August 3, 2015